The inequity of climate change is something that’s absolutely unavoidable on an international scale. The rich countries of the world have emitted the most over time, while the poorer countries of the world are currently bearing the brunt of climate change’s effects. I was lucky to be able to attend the UN Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany this week. This post is going to give a very high level overview of the equity scene at the international level - the actual conference proceedings are far more detailed than this and involve a lot of discussions of specific language of decisions and procedural things.

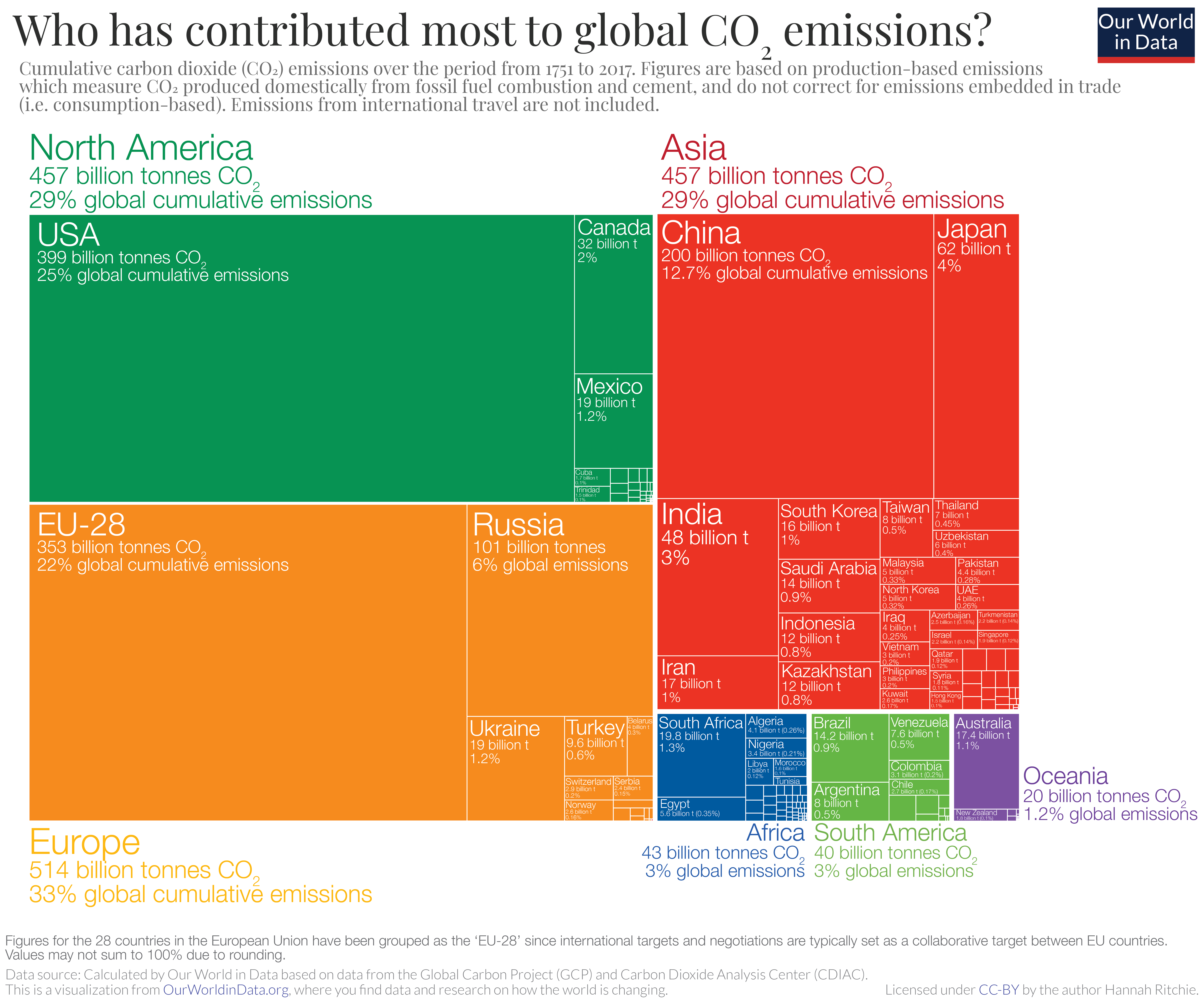

Rich countries are responsble for historic emissions. From Our World in Data.

Being at the Bonn conference this week, discussions of equity were everywhere. One of the main activities in Bonn was completing the technical phase of the Global Stocktake (GST), part of the ‘ratchet mechanism’ of the Paris Agreement (the one where they agreed to limit warming to below +2C (3.6F)) to help countries increase ambitions over time. Countries submit their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), saying what they’re going to do to reduce their emissions. This follows the principle of CBDR-RC, Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities. That is UN speak for all countries have a responsbility to fight climate change and reduce emissions, but each has different capabilities to accomplish that and different responsibility for the current mess, i.e. historic and current emissions. The Paris Agreement solidified that developed countries are expected to lead on mitigation (reducing emissions) and finance (for helping other countries).

The US is responsible for 25% of all cumulative emissions. From Our World in Data

Following that, developing countries have been asking for loss and damage funds to help them deal with the damages that rich countries have essentially inflicted on them by making climate change (the same way that someone who started the fire that burned your house down should pay for repairing your house). At COP27, the last climate conference in November 2022, there was an international agreement that developed countries should indeed provide funding mechanisms to compensate for losses and damages in developing countries from climate change. At the current Bonn talks and continuing at COP28 in December, countries are trying to decided exactly what that means. Potential proposals include taxing windfall profits (unusually large profits) of fossil fuel companies (e.g. due to the energy crisis, oil and gas companies made an extra 2 trillion USD in 2022 compared to 2021 through no extra effort on their part) and directing that to the fund, or putting a small tax on all international flights. There’s still discussions being held at Bonn. Developing countries want a separate fund specifically for loss and damage. Rich countries are not so keen, and also only want to be funding truly developing countries, not emerging economies like China and Saudi Arabia that are high emitters.

Separately from loss and damage, developed countries committed back at COP15 in 2009 to providing 100 billion USD per year in climate finance (grants, loans, and other financial mechanisms) to developing countries by 2020 for the purpose of both adaptation (adapting to climate change and the things it brings) and mitigation (reducing emissions). Countries have, so far as of 2020, only provided $182 billion in total (so falling very short), and some of that is really a stretch for being climate related according to a new report by Reuters, including money from Japan going to a coal plant in Bangladesh, Belgium funding a movie set in the rainforest, the US backing a hotel in Haiti, and Italy financing chocolate shops in Asia.

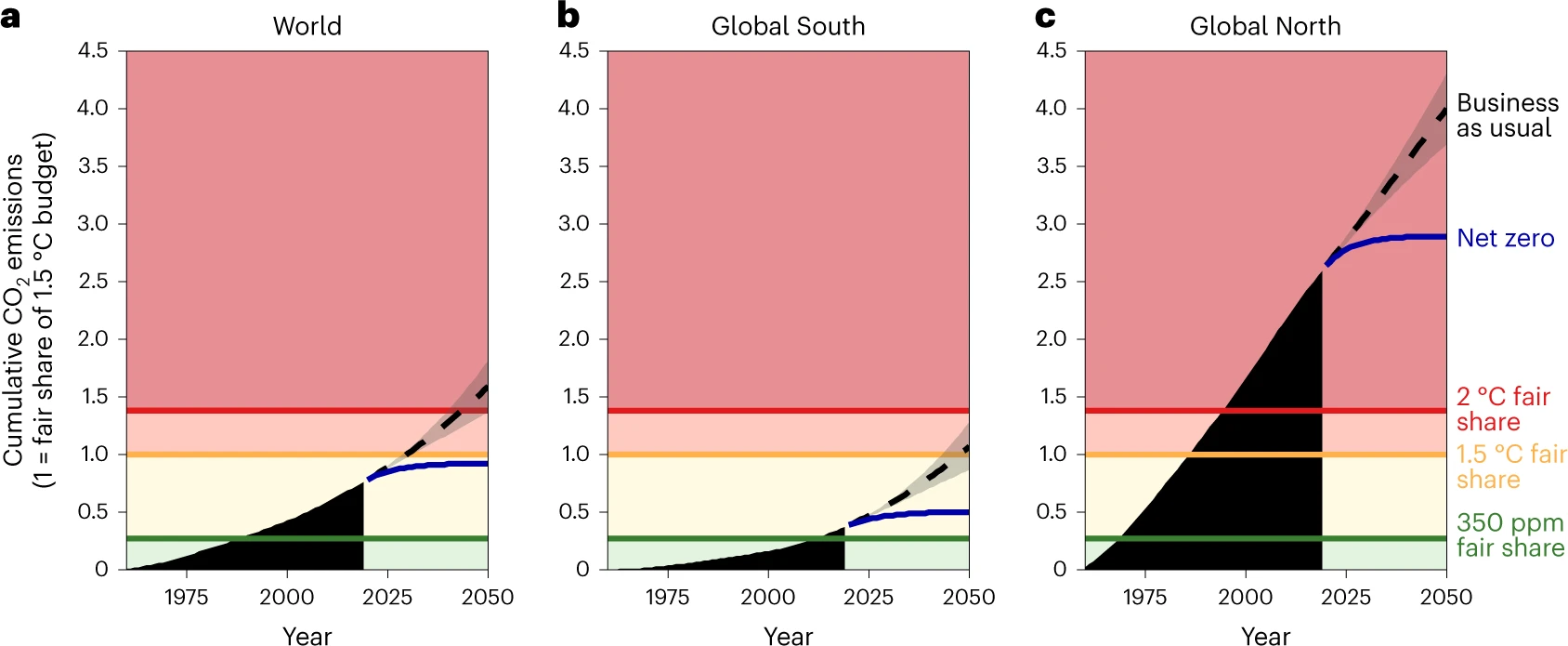

Because of the lack of action, we are likely crossing +1.5C (2.7F) before 2027. We have to peak and start declining emissions before 2025, 18 months from now, if we want to have at least a 50/50 chance of not hitting +1.5C. That means we have a very finite carbon budget (<250 bn tonnes CO2 as of this year, and we currently emit about 54 bn tonnes per year according to this very recent paper) that we need to make last as long as possible. Right now, emissions are still extremely uneven, so the question of equity and emissions is increasingly urgent.

The US continues to lead oil production. From Our World in Data

The things that really struck me in listening to positions from different countries in one of the plenaries I attended was still the avoidance of responsibility by some rich countries. Both the US and Australia made a point to say that their historic emissions should not really add to their responsibility to cut current emissions because those emissions came from a time when there weren’t viable energy alternatives and we didn’t know any better (debatable, especially since we have known about climate change since the middle of the last century, but sure). They also patted themselves on the back for helping develop the technologies that can help us cut emissions. Their stance is that everyone should be doing the best they can with their current abilities and highest possible ambitions to cut emissions, following the CBDR-RC principle. According to that logic, shouldn’t we the rich countries, the ones who have the most current ability to invest in the needed change, have the most dramatic emissions cuts in the near future? Yet, we are still investing in and allowing new oil and gas, and a new study estimates that developed countries are going to take more than 3x of their fair share of the remaining budget and could owe developing countries $170 trillion for that (see below and the article in Nature). India made the point very clearly in one of their remarks that continuing to develop fossil fuels in developed countries is against the Paris agreement for 1.5C as well as equity principles. Most developed countries did not meet their pre-2020 goals. The multiple levels of hypocrisy are really disappointing; we caused this problem, we haven’t stopped making it worse yet, we aren’t helping other countries like we said we would to take action, our and we aren’t doing much to make up for the damages we caused and continue to cause.

P.S., the modeled scenarios we are basing all the negotiations on are not even equitable. The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which does all the climate science and models and creating scenario pathways for our economics and emissions) models from the latest report (AR6) actually don’t even work towards a more equitable future. According to Hickel and Slamersak (2022 in The Lancet), the scenarios for a < 2C (3.6F) future on average maintain rich countries’ privileges and use 2-3 times more energy per person than the developing countries are allowed for the rest of the century. The scenarios also rely heavily on bioenergy negative emissions technologies like BECCS (see this post for an explainer) to make this work. BECCS is highly land intensive, so these scenarios then also rely on using (colonizing, some would say) land in developing countries to support the intensive energy use by rich countries. Models are just models and are usually wrong, but if the best models in the world aren’t even putting forward possible scenarios of energy and emissions equity, what are the chances we can shape our real world in that direction?

Overall, it was super interesting to be able to go to a small part of the Bonn Climate Change Conference, thanks to my master’s program at the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, which I am studying thanks to Fulbright. Thus, I need to say that these views are entirely my own and do not reflect any of these institutions.